Read our latest research about having better conversations with teenagers in this post.

If you’re a parent, you might recognize the following scripts:

Parent: How was your day?

Teen: Fine (as he walks off to his room).

Parent: Who are you texting?

Teen: No one (as she continues to look down and type).

Parent: (After observing her teen chatting online for quite some time) What were you talking to your friends about?

Teen: Nothing (as he shuts the door to his room).

At times like this, parents can feel frustrated and hurt, especially when teenagers treat parents like they are people to be endured rather than embraced.

These kinds of exchanges can be not only unsatisfying but also damaging to our relationships. As my daughter Yumi and I have reflected on how parents and adolescents both contribute to breakdowns in communication, it reminded us of tennis. Using a tennis metaphor for what happens in our conversations, we have written a three-part article series to offer insights and practical tips from a teenager’s perspective (Yumi) as well as from a mom’s and psychologist’s viewpoint (Susan).

Preparing to Converse: At Baseline

Yumi’s View

Many of my friends share that their parents don’t know or understand them. They think their parents do not even try.

Instead, parents seem to talk at teenagers about what they want from them. I have a friend who just confided in me that the only thing her dad talks to her about is grades, and she feels frustrated, hurt, and disconnected from him. My friend and I were thinking that maybe this is the only way he knows to connect with her. Perhaps many parents do not realize that this is how they come across to their teenagers. Or maybe some parents simply do not know how to communicate.

When I first learned to play tennis, I had to know all of the components of the tennis court as well as the rules of the game before I could play. I was taught to hit all of my shots within the boundaries of the court in order to win a point. I learned that the baseline is where I prepare to serve or receive a serve at the beginning of each game. For instance, when I am getting ready to receive a serve, I have to stand in ready position at the baseline: knees bent, weight slightly forward, racket up and in front of my body, eye on the ball, and mind focused. If I am not ready to play, I will most likely lose the point and perhaps the game as well.

In many ways, what happens in tennis parallels conversations between parents and their teenagers. In tennis, we have to know the game. In our families, we have to know each other.

In tennis, I have to know where to hit the ball in order to win. There are clear lines that I should not cross if I want to score. It is the same in parent-teen relationships: If parents want their kids to talk to them, it’s important that they communicate within the boundaries of what is respectful and loving.

If my mom and I do not really know each other, then our talks will feel superficial. When we aren’t considerate of each other’s feelings, we end up hurting each other. And when I want to express my thoughts and feelings, but my mom is not focused on what I’m sharing, I feel like walking out of the room altogether. All of these can result in lost opportunities to connect.

Susan’s View

People speak an average of 16,000 words per day. Of these, parents may use hundreds of words each day to communicate with their teenagers.

This raises some questions for me as a parent. What percentage of our family’s conversations is about getting to know each other more? What percentage of our conversations consists of words that are disrespectful and hurtful? What percentage of our conversations indicates a readiness to hear one another?

The average parent wants to know their kids and to be available to dialogue with them. Most do not intend harm. In fact, we love our kids; we want what is best for them. We are often willing to sacrifice ourselves to ensure that they are healthy and happy. However, these thoughts and feelings are not communicated well when we spend much of our time lecturing, making discouraging comments, withholding permission for their requests, and threatening them in order to control their behaviors.

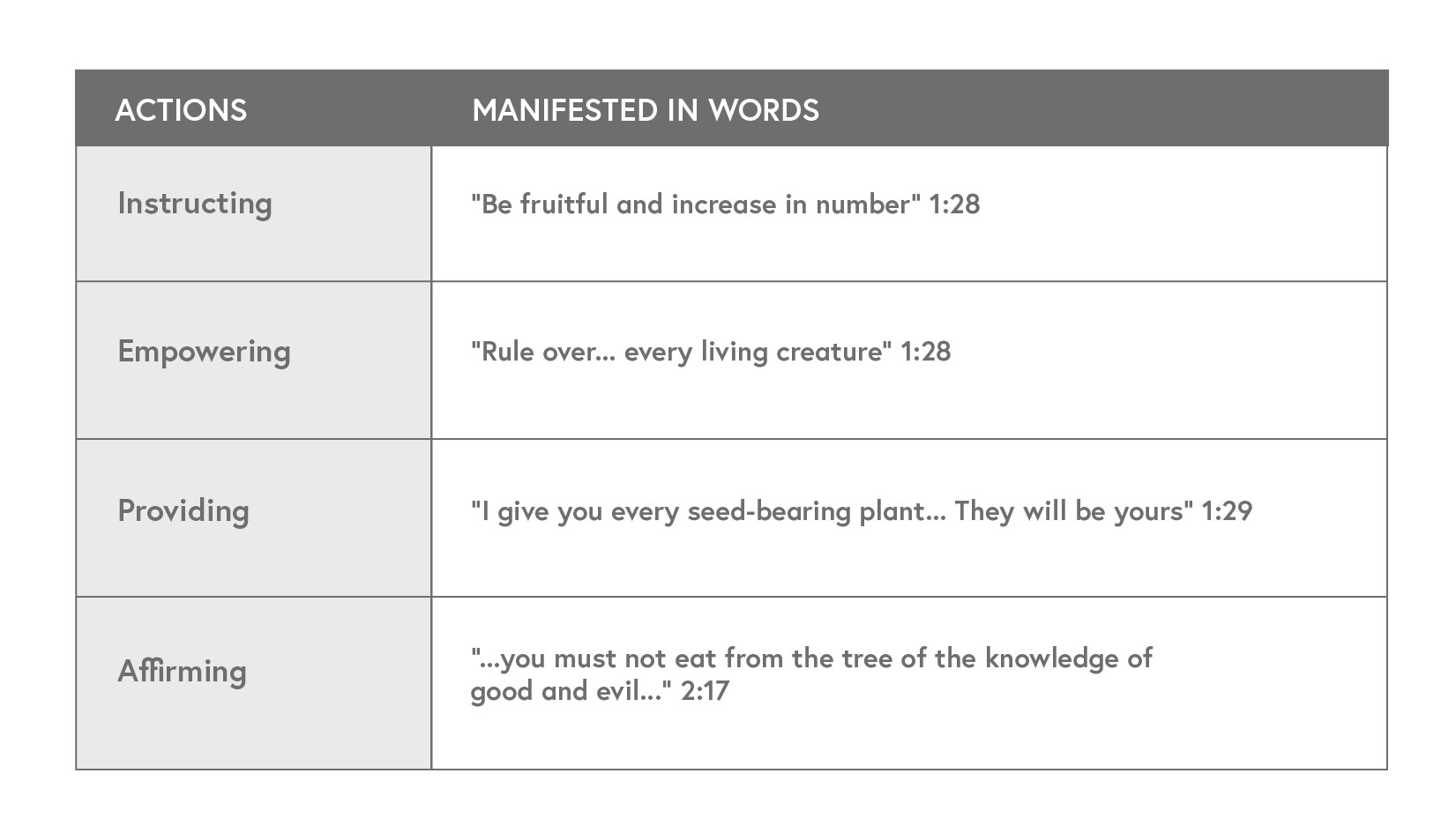

Let’s take a look at a model of a parent who connects authentically and positively with his children. From the very beginning in Genesis, God relates to humanity in the following ways:

The story of our relationship with God begins with words that instruct, empower, provide, affirm, and set limits – words that help us thrive rather than fail. These words set the tone for the unfolding of events and interactions in human history.

Of course we can’t measure up to God as parents. However, God calls us to be a reflection of him to the world. This means that by God’s grace and strength, we need to parent our children as God has demonstrated in parenting us – through words that forge a healthy connection.

Growing in communication with our children

If you’d like to grow in your communication with your child, take some time to record how you communicate with them at the end of each day for one week. Chart the following types of communication: instructing, empowering, providing, affirming, as well as lecturing, discouraging, withholding, and threatening words/behaviors. Here is a template you can use to record your words and behaviors:

Obviously, there are other ways parents and teenagers relate as well. You can add more behaviors based specifically on what occurs in your conversations with your kids. Keep track of how you communicate with each child separately. It is important to know if you interact differently with each son or daughter (we often do as parents, even though we like to think we’re consistent). Being aware of differences can lead to changes tailored to each relationship.

As you track the types of communication you have with your teenagers, ask them also to record the number of times they experience the same behaviors from you over the same week. How well do your observations match? Having both self- and other- reports keep this exercise from being too subjective, which can limit its usefulness.

If you are predisposed to looking at yourself more critically, you might be coloring what happens more negatively than your child experiences it. You might record that you have “discouraged” more than you really have. On the other hand, you might be filtering your experiences more positively. In this case you might log that you have “empowered” more than you actually have done so. By having both you and your teenager monitor what happens, you increase the likelihood that you are getting more accurate information. The truth about what is happening is probably somewhere in the middle of yours and your teen’s perceptions.

Here’s one example of how Yumi and I have experienced this recently:

Yumi: I feel like having almond macaroons. Can we make some?

Susan: Sure! (Happy that Yumi initiated spending time together)

Yumi: I’m going to get everything we need.

Susan: Okay… Why don’t you use that pan? How about this measuring cup? Do you want to use this bowl or that one?

Yumi: Stop! It feels like you’re rushing me.

Susan: Sorry… I didn’t mean to. (After a while…) Wouldn’t it be better if you prepare the eggs first? How are you planning to grind the almonds?

Yumi: I got it mom. Now I don’t want to do this with you anymore.

In the above conversation, I could chart that I was “instructing” and even “empowering” Yumi by asking questions for her to make decisions. Yumi might describe my behaviors as “lecturing” and “controlling.” Once I understand Yumi’s experience – which is different than what I intended – I can recognize how my questioning can ultimately lead to disengagement.

As Yumi and I have learned, once you become aware of this type of communication with your teenager, you can change your behavior in order to connect better with each other. In fact, just the act of monitoring your interactions can affect positive change.[[Abraham, C., & Michie, S. (2008). A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychology, 27(3), 379-387.]]

In part 2 of this series, we focus on how to start a conversation that feels positive to both parents and their teenagers.

Action Points

-

Begin recording your words and actions on a chart like the one shown above, then tally how often you repeat certain ways of engaging. Ask your teenager to also record their impressions of your responses. Keep the focus on your behavior for now, not theirs.

-

Initiate a conversation to debrief your chart together, and look together at where you agree and disagree about particular interactions. Try to avoid defensive responses and just listen to your teenager’s actual impressions of your communication.

-

Talk over your findings with your spouse and/or a close friend. You may want to set a goal of changing specific kinds of responses. If you do so, check in with that person (and with your teenager) every week for a month to see how it’s going.

Unlock the potential of the teenagers you care about most

The teenagers in your life are searching for answers to their 3 biggest questions:

Who am I? Where do I fit? What difference can I make?

Kara Powell and Brad Griffin tap into new research to equip you with essential tools to relate to the young people you care about.

More From Us

Sign up for our email today and choose from one of our popular free downloads sent straight to your inbox. Plus, you’ll be the first to know about our sales, offers, and new releases.